The Virtues of the Back of the Envelope

by Dave Lampert, Guest Blogger | B2B Advisor

Since the coronavirus ate my job earlier this year, I’ve been splitting my time between searching for my next opportunity, advising several start-ups, and volunteering at a local food pantry where demand has increased 10X since Feb. I’ve also been doing a lot of reading, some business-related, some not, and recently reread one of my all-time favorites, Norton Juster’s underrated children’s classic, The Phantom Tollbooth.

Milo’s Magic Staff

The Phantom Tollbooth tells the story of a small boy, Milo, who “didn’t know what to do with himself” until a mysterious tollbooth one day appears in his room. Milo’s tollbooth leads him to an uncharted kingdom on a quest to rescue the Princesses Rhyme and Reason from their banishment to the Castle in the Air, reachable only through the Mountains of Ignorance.

Early in his journey, one of the kingdom’s rulers, the Mathemagician, gives Milo a magic staff that performs calculations, and it proves invaluable when Milo and his companions are waylaid by the Terrible Trivium as they near the end of their quest. This deceptively harmless-appearing character sweet talks the travelers into performing a “few small tasks,” which include moving a huge pile of sand using tweezers, and emptying a well using an eye dropper. After working away with little progress, Milo takes out the magic staff and calculates that it will take them 837 years to complete their work. Armed with this knowledge, they quickly abandon the time-wasting tasks, and get on with their quest.

The moral? It pays to “Do the Math!”

A Walk in the Woods

I recently went hiking with my 17-year-old son on the Appalachian Trail (AT) before he left for a gap year. Facing the requirement to wear a mask when passing other hikers, we tried to figure out how many hikers we might encounter, so we could determine whether: a) to keep our masks on all of the time; b) wear them around our chins most of the time and adjust when needed; or c) keep the masks in our pockets and pull them out only when we encountered other hikers.

We follow a “no phones rule” (photography excepted) when hiking, so we had to make the determination using only the data that we had, or could reasonably estimate. The exact number didn’t matter - our decision required an order-of-magnitude estimate. If we were going to pass 5 hikers in a couple of hours, we could keep the masks in our pockets. 50 hikers would dictate the chin-strap method, and 500 hikers meant wearing them the whole time.

Luckily, my son had been planning a 3-week AT trail hike as a senior project, and knew that about 3K people thru-hike the 2200 hundred miles each season, and that about 5M day-hikers typically enjoy a short section of the trail each year. From there, some simple math (length of trail divided by average length of hike, # days in season, adjustments for the weekend and a busy section, etc.) led us to believe we might encounter only around 10 – 20 hikers, and we happily set off with the masks in our pockets.

Luckily our hike didn’t require a magic staff, as we could do “good enough” calculations in our heads, using what we knew and could estimate. But the moral is the same, it pays to “do the math!”

Doing the Math in Business

Reflecting on these back-to-back incidents highlights for me the value of “doing the math” and using rough estimates in the business world, when complete and accurate data is often not readily available, and can be too time-consuming and/or expensive to source. One area where this comes up frequently is market sizing.

I was recently speaking with the founder of a start-up, discussing which market segment they should focus on, given limited resources, and asked the founder about the sizes of the segments. She apologized for not having hard data. “No worries,” I said, and suggested that we work together on estimating the Total Addressable Market (TAM) of the three potential segments sales achievable, and the time, and money, to get traction in each segment.

It turned out that working together and using just the few data points she had and best estimates on other numbers, we were able to get to order-of-magnitude estimates on the size of each of the three segments, and a clear winner emerged as to which segment to pursue first. Once again, basic math and rough estimates combined to provide the strategic direction required.

Doing the Math in Business, Part II

A few years back, I joined a software company and discovered that a large base of customers were still using the legacy “on-premise” version of our software, while paying an annual maintenance fee of 20% of the original purchase price. This looked to me like an opportunity to grow revenue by increasing the pricing on our maintenance fees, but the Founder & CEO was concerned we might lose customers.

Yes, I replied, we may very well lose some customers, but we’ll likely more than make up for the losses through the increased revenue we’ll see from the other customers. And the customers we were most likely to lose were going to be low-value customers, and less likely to migrate to our new SaaS product anyways.

A few quick calculations on the white-board illustrated that we would need to incur a loss of more than 30% of maintenance-paying customers to offset the revenue gains we’d see from those who accepted the price increase as proposed. Of course, we could potentially selectively roll back or reduce the increase for the small number of high-value customers who might push back. We ended up going ahead with the price increases, cancellations were minimal, and several hundred thousand dollars flowed straight to the bottom line.

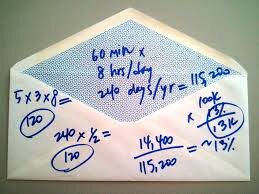

It’s worth noting that in each of these examples, no complex financial models or even spreadsheets were necessary. And while envelopes may be harder and harder to find, simple math can be done either in your head, on the white-board, or using the calculator app on your phone. Good luck!

Dave Lampert leads and advises lower middle-market B2B Information Services, Software and SaaS companies.